Frontispiece of Giambattista Vico’s La Scienza Nuova, 1730 ed.

On a scale of one to 10, how complex is contemporary Japan? How about ancient Rome? Neolithic settlements in the Niger Delta? Does the presence or absence of “Informal Elite Polygamy” give you the entire picture of gender relations in a given society? And would you trust a machine learning algorithm that used this data to predict our future? Some researchers are claiming that we should do just that, and even hope that we can use them to make policy recommendations addressing the great issues of our day — climate change, economic inequality, mass migration, you name it.

A massive databank created by University of Connecticut professor Peter Turchin aims to collect our knowledge of past cultures in a “systematically organized” fashion in order to test theories that explain “cultural evolution and historical dynamics.” If you think that sounds like a pretty scientific way of describing traditionally humanistic disciplines like history and anthropology, you’re right — a recent Guardian profile portrays Turchin, a professor in the departments of mathematics, anthropology, and evolutionary biology, as an empiricist gatecrasher who can rescue the field of history from its myopic decadence. After a successful career as a biologist, he began to think about the ways his methods could benefit the field of history, writing a book called Historical Dynamics in 2003, and in 2011 founding a journal, Cliodynamics, dedicated to the “mathematical modeling of historical processes.” Gathering an interdisciplinary group of like-minded researchers around him, he began to collect huge amounts information about our past in data form; this endeavor has borne fruit beginning in 2018 in the form of publications in Cliodynamics and other journals.

His project, named the Seshat Databank after the Egyptian goddess of wisdom, knowledge, and writing, represents a new iteration of an old story: scientists thinking that humanists and social scientists could learn a thing or two from them about methodological rigor, in this case exemplified by a growing trend of researchers advocating the use advanced data science tools in those disciplines.

The databank project, which is partially open to the public, is built on the foundations of complexity science, a field of study that relies on mathematical tools to discover interactions in systems that are too, well, complex for us to fully comprehend. The seemingly random vicissitudes of the weather, or the rise and fall of great civilizations, are revealed to follow regular patterns when viewed at a large enough scale. Collecting data on everything from agricultural tools to bureaucratic infrastructure in societies all over the globe and throughout history allows computers to perform millions of calculations, searching for mathematical interactions among the parts of the complex systems the data describes. And turning history into a data set is theoretically possible, because anything — not only something like population estimates, but also language and archaeological findings — can be converted into numbers and interpreted by computers, which can do math much faster than puny human brains.

What this project and others like it will ultimately reveal, however, is not laws that govern the course of history, but rather the inability of data itself to capture the truth about history and humans in general, whether or not the theories of complexity science are correct. While the researchers can use technology to find complex interactions within their data, the data itself radically simplifies concrete realities, no matter if it is collected for scientific or commercial purposes. Instagram might record that you liked a photo, but the platform doesn’t know why: maybe you felt obligated, or maybe your finger slipped. That doesn’t stop it from making all sorts of tools that rely on the assumption that your “like” means that you liked the picture. Data is always an abstraction, a representation of some real phenomenon that cannot be fully captured by numbers. To fetishize data and imbue it with an almost magical capacity to describe our lives only mystifies the ways it functions in the world today.

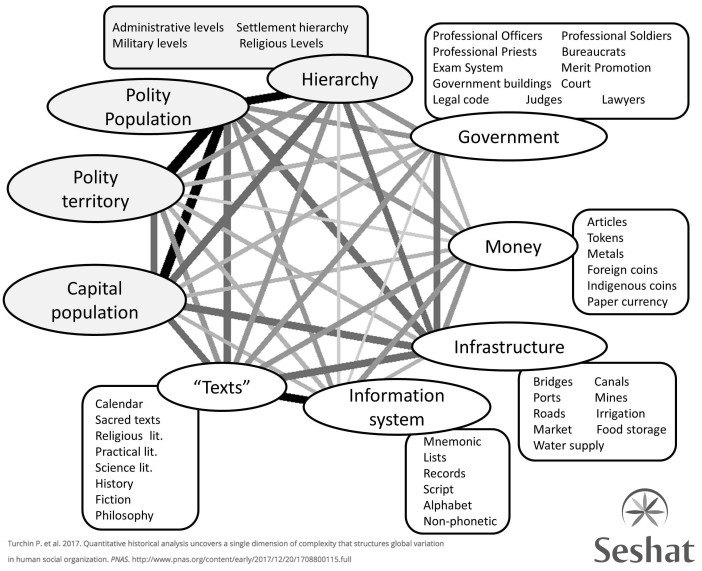

The Seshat view of a society. Source

To Turchin’s credit, he doesn’t display the typical STEMlord contempt for the humanities — in his papers, he generously cites anthropologists and sociologists, while simply arguing that he wants to use data to test and validate their theories in a more rigorous way. In fact, the project that he and his colleagues describe is rather less ambitious than what is written in the Guardian article, perhaps because it is meant to lay the groundwork for future progress. Regions of the world throughout time (beginning around 10,000 years ago, in the Stone Age) are sampled and assigned variables which capture various aspects of its social development, including social/political structures, economic systems, and cultural practices. This produces a dataframe, essentially an Excel file, which can become the basis for all sorts of mathematical operations.

They then employ the same kinds of statistical methods commonly employed by tech firms to predict, say, what kinds of ads achieve the best conversion metrics. But the Seshat dataset is about learning from our past, not boosting KPIs, and Turchin’s team uses it to test hypotheses about historical change by looking, for example, at the factors that influenced the development of information systems throughout the world. This in turn allows the researchers to form conclusions about social “evolution” — they love that word — which have the flavor of objective truth because they are the products of the scientific method. And these truths have a specific use, according to Turchin; in the Guardian profile, he holds that societies go through cycles of stability and crisis, and that his analysis can not only predict when a crisis is likely to occur, but also prescribe therapeutic interventions that can ameliorate or cure them.

Turchin’s theory thus represents a rejoinder to the dominant mode of academic history, which rejects any idea of underlying structure or universal law governing human affairs. Historians nowadays prefer to look at specific times and places in history, in the hope of understanding more deeply how human life is conditioned by the economic, political, social and cultural contexts surrounding it. This can tell us about what it means to be a human, but it does not reveal much about large-scale patterns in the development of our societies.

Then again, the idea that history moves in cycles is as old as the discipline itself. Herodotus, the first historian in the West, adapted a nested cyclical structure from the Iliad in order to give his Histories its epic heft. Aristotle and Polybius held that states undergo a process where monarchs become decadent and are overthrown by the aristocracy, only to be overthrown by the people after they decline, with a final descent into anarchy that is ended by the rise of a new monarch. Ibn Khaldun presented yet another cyclical model of social and political change in Islamic Golden Age, wherein civilized cultures become soft and fractious, eventually suffering conquest by hardened, unified nomadic groups from their periphery. Modern readers may be familiar with Marx’s idea that the dialectic of class struggle results in regular periods of social conflict.

But for better or worse, professional historians focus on understanding how people lived in the past while tending to avoid The Meaning of It All. The attractiveness of Turchin’s project might be in its appeal to a more popular understanding of history, which is that it does have a structure which can be understood, and that its lessons can be extended into the future. As Turchin himself explained in a recent blog post addressing criticism of his project, he does not conceive of it as a “threat” to history, but rather as a continuation of comparative historical research in the mode of Polybius and Ibn Khaldun. There’s a lesson for the professors there, I think, although not necessarily the same one Turchin is offering.

That the Seshat project addresses a certain desire for deeper meaning in history is one thing; its claims of objectivity, scientific rigor, and generalizability are the real problem. The “complexity science” upon which the whole endeavor rests claims that computers can “discern patterns not visible to the human eye,” in the words of the Guardian. This is certainly true, but also ignores one of the cardinal rules of machine learning: garbage in, garbage out. This means that, even though your algorithm may perform admirably, if your data is bad, then the model is useless.

It is clear that Turchin and his colleagues took great care in putting together the Seshat Databank, but that doesn’t change the fact that it represents a collection of assumptions and educated guesses about the relevant variables in “historical dynamics.” Not only do the researchers have to decide what aspects of past cultures are important enough to be measured, they also are forced to turn our complicated and often incomplete knowledge about the past into simple numbers. You could write a million words about Italy in the 15th century and not capture all the variation and complexity there, to say nothing of all the things we will never learn about the topic, because they are permanently lost. But at least historians are aware of that, and temper their interpretations of the past with an awareness that they are looking at it with modern eyes.

The Seshat researchers would probably reply that the point is not to understand any one culture in depth, but to use the advantages of scale offered by computers to deduce trends. Other projects use a similar logic. One digital simulation of society — in which blocks of code interact with one another following rules which approximate human behavior — might not be that useful, because it is so abstracted from our reality, but run millions of them, and you might learn some insights about how a city is likely to respond to an influx of immigrants, as a recent article in New Scientist claimed.

Then again, it’s worth asking what’s the point of that point: How useful are these projects actually? Turchin also wants to run computer simulations to see which kinds of societies are more likely to collapse under certain stressors like foreign invasion or natural disaster, and also which kinds of interventions save them. I think that this project reflects and flatters the attitudes of elite liberals, who see society as akin to a human body — a complex system whose periodic crises (crisis being originally a medical term, as in “the patient is in critical condition”) should be managed by credentialed experts. A fine idea, if we set aside the fact that it ignores the political will of the vast majority of people. But what if the experts are wrong?

Both tech-optimists and their critics live in thrall to data fetishism. They imagine that access to, and mastery of, the vast reservoirs of data out there can confer supernatural powers — omniscience, omnipotence, and even the ability to create new life. The hype around technology’s ability to prevent the kinds of catastrophes that marred our past reflects the mystique that data currently enjoys. But our Google searches and Facebook likes are not portals into our innermost selves; more often, they are likely to reveal that you are interested in buying a refrigerator, or whatever. That’s mostly what our data is used for, and even then, not always effectively, as when you constantly see refrigerator ads, even though you just bought a Frigidaire last week.

But what the concept of data fetishism captures is not only the magical properties ascribed to our browser cookies and the like. It also gestures to the status of data as a commodity — “the new oil,” as the cliche goes. As in Marx’s concept of commodity fetishism, magical thinking about data not only secures its status as a source of profits, but also obscures the mundane and often exploitative social relations that go into its production and analysis. And what is history but a record of mundane and often exploitative social relations?

In other words, the Seshat Databank is less a “systematically organized” collection of all historical knowledge than a recording of user inputs by the researchers themselves. Their assumptions and biases — themselves shaped by historical conditions — imbue the dataset, but are hidden from view, Oz-like, by the screen of scientific objectivity. That’s to say nothing of biases inherent to the historical record itself, which is fragmentary and distributed unequally across cultures. So we ought to be circumspect about their claims of eventually solving the myriad crises facing us today. Because we are not abstractions, nor is the world we inhabit.